Why Consider Dividend Stocks During Market Volatility?

As an investor, you basically have two ways to make profits with stocks. The first is to follow the well-known principle: buy low and sell high. The second way, which is the subject of this article, is to buy dividend-paying stocks.

Introduced by the Dutch East India Company at the very beginning of the 17th century, dividends have since enjoyed resounding success with followers of the buy-and-hold strategy and are certainly worth looking into. But, how to become an expert on stocks?

What Is a Dividend?

Dividends, whether historical or current, are the subject of particular attention by many investors when it comes time to choose their investments.

They represent the share of profits that a company pays to its shareholders. Since they are “passive income”, they are a fundamental part of a long-term investment strategy. Dividends are usually distributed to shareholders quarterly, but their frequency varies by industry. Their value can range from a few cents to tens of dollars per share.

When you get your dividends, you can either cash out the money or use it to buy more shares of that company.

The company’s board of directors sets the amount and frequency of dividend payments, but shareholders must agree.

A reduction – or, worse, the interruption – of dividends can be very bad news for all parties involved. This indicates that the company’s financial situation could be precarious, whether due to growing debt or declining revenues, which would negatively affect the share price.

If a company finds itself unable to pay all the dividends due, the available payments are distributed according to an established hierarchy. Creditors (bondholders) come before shareholders, a category in which preferred shareholders are distinguished from ordinary shareholders, the former having priority. Also check out, can dividend stocks make you rich?

Is Volatility Synonymous with Risk?

In the financial services sector, volatility gets bad press. For the average investor, it is synonymous with risk and you will often see the two terms used interchangeably.

This reputation is not entirely unfounded. Obviously, on a short-term horizon, a feverish market can have concrete consequences if you have to buy or sell an investment. If so, what may seem slightly volatile to another investor is downright risky to you. However, volatility is not an effective measure of long-term risk. Have a look at Warren Buffet words on volatility & risk.

“Lesson in Wisdom” about Volatility

Often represented as standard deviation in finance, volatility is a statistical measure of how much the price fluctuates up and down over a period of time. Investments that fluctuate rapidly and dramatically in price are considered highly volatile investments. Those whose prices are stable and rarely change are considered low-volatility investments.

The formula for calculating standard deviation treats volatility in one and the same way. It tells you how much the results have deviated, up or down, from the historical average. Thus, an investment that has always recorded positive returns may, despite everything, display high volatility if these results have varied from slightly positive to strongly positive. Simply put, volatility measures how well a security trades and not necessarily how much business risk it represents.

Consider the following example. Company A’s stock shows no volatility, but provides a false sense of security as, over time, the stock price has gradually declined to near zero. On the other hand, the stock of Company B, whose price fluctuated greatly in the short term (uncertainty), shows an upward trend in the long term.

At the Heart of the Matter

What explains these upward and downward movements? Volatility may indicate that market participants are making emotional rather than rational decisions. History has shown that in the short term, stock markets do not operate on mathematical principles, but rather on behavioral psychology. The technology bubble is a clear example where emotions have taken over the judgment of investors. More recently, the sovereign debt crisis rocked markets around the world and again increased volatility.

It can become a vicious circle. Investors react to short-term “rumors” like alarming headlines and the opinions of industry bosses, and buy or sell stocks on the spur of the moment. Investors then react to these market moves, creating – you guessed it – greater volatility. All too often the greatest risk investors face comes not from external forces, but from their own behavior.

A Different Definition of Risk

Low volatility does not necessarily mean an investment is safer. Similarly, an investment can be volatile without being risky. This is why sophisticated investors do not see volatility as a risk. Instead, risk should be viewed as the possibility of permanent capital loss. In other words, the price of a share collapses and remains at a very low level for a long time, if not forever.

In the past, such an event coincided with periods of consensus. For example, in the 1980s, investors believed that Japan would become the world power. It was fashionable to copy the Japanese because they knew how to run businesses. If you invested based on this theory and bought the stocks of the Nikkei index, you still have not recouped your losses.

Looking back to the 1990s, everyone was saying that emerging economies like Mexico would be the fastest growing. The situation changed in the middle of the decade during the Tequila crisis in 1994. In 1998, emerging markets from Russia to Southeast Asia all but collapsed.

During the ensuing tech bubble, investors clung to the false promise of meteoric growth for internet businesses. These unrealistic expectations were fueled by the “irrational exuberance” of the market. When the bubble burst, billions of dollars simply flew away.

Not too long ago, investors lost large sums during the 2008 financial crisis in the false belief that real estate could only go up because that was what everyone said.

In all of these situations, people who followed the consensus suffered capital losses and still haven’t gotten their money back. Therefore, it is safer to take the good old fashioned approach to risk by asking the question: “How much money can I lose and how likely is that to happen?”

The real risk comes from a disruption in the underlying fundamentals of an investment. For this reason, an in-depth knowledge of the company is a much better way to control risk than studying the stock price. This means focusing on business-specific risks, such as increased competition, shrinking margins, the competence of the management team, and the assessment of the company in relation to its true potential. By following this approach, investors are able to make good decisions despite volatility.

Let’s say 100 people are asked to estimate the price of a new pickup truck. Most of them would price it somewhere between $25,000 and $45,000, and they’d be right. Now let’s say the van is offered at a price of $200 to those 100 people. They would certainly all accept the offer and none of them would have trouble sleeping thinking they paid too much for the van.

Imagine asking those same 100 people if the price of shares of a public company is $50, $100, or $300 each, what would happen if that company’s stock price fell due to negative macroeconomic news that has no bearing on the company’s underlying value? Almost all investors would probably rush to sell their shares.

This is why it is important for an investor to know the value of a company because it can have an advantage over others who do not know it. The focus therefore needs to be on business-specific risks, such as increased competition, shrinking margins, the competence of the management team, and assessing the business against its true potential. By following this approach, investors are able to make good decisions despite volatility.

As Ben Graham liked to say: “In the short term, the market is like an instrument to vote, but in the long term, it is an instrument to weigh.” Having a stake in a company – not just shares – should keep your investments on track and give you peace of mind during periods of volatility.

Conclusion

In summary, volatility should not be viewed as a risk. It may seem like a risk, but in fact it is not a risk in its own right. The real risk is the possibility of permanent capital loss.

Markets around the world offer a wide variety of dividend-paying stocks in a multitude of sectors: telecommunications, real estate (REITs), healthcare, financial services, utilities, consumer staples (eg. packaged goods), etc.

Basically, stocks of companies that pay dividends are a bit safer than growth stocks. Often less volatile, they can help diversify a portfolio and reduce risk. This explains why investing in dividend-paying stocks is a very popular investment strategy among more traditional investors or those who prefer to buy for the long term.

Aside from the risks of dividend cuts (discussed above), dividend payments are generally reliable, unlike a stock price. And that’s without forgetting capital gains, which are often higher for dividend-paying stocks than for others.

When looking for stocks with strong dividends for your portfolio, it’s obviously wise to find out about the history of companies’ dividend payments. Go back ten years, or further. Do dividend payments stay the same or do they increase year after year? Have any been omitted, or have their amounts been revised downwards? Do these and you’ll be able to ride the waves and make a well informed decision.

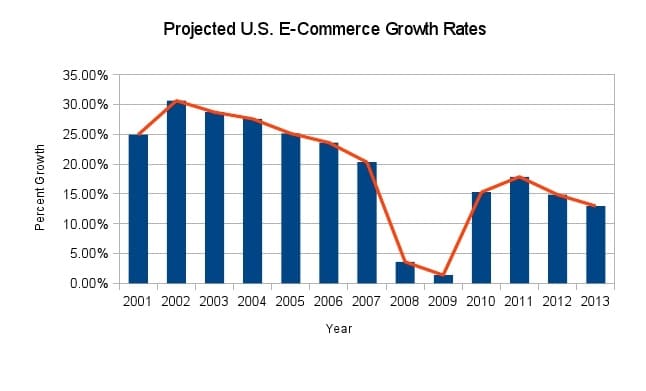

(Image credit: Yahoo Finance)